During the 3rd and 2nd Centuries B C the Romans Adopted This Style of Art

The fine art of Ancient Rome, its Democracy and later Empire includes architecture, painting, sculpture and mosaic piece of work. Luxury objects in metal-piece of work, jewel engraving, ivory carvings, and glass are sometimes considered to be minor forms of Roman art,[1] although they were not considered as such at the time. Sculpture was mayhap considered every bit the highest class of art by Romans, but figure painting was besides highly regarded. A very large body of sculpture has survived from nigh the 1st century BC onward, though very little from earlier, merely very little painting remains, and probably nothing that a contemporary would have considered to be of the highest quality.

Aboriginal Roman pottery was not a luxury production, but a vast production of "fine wares" in terra sigillata were decorated with reliefs that reflected the latest taste, and provided a large grouping in society with stylish objects at what was evidently an affordable price. Roman coins were an of import means of propaganda, and have survived in enormous numbers.

Introduction [edit]

Left image: A Roman fresco from Pompeii showing a Maenad in silk dress, 1st century Advertizing

Correct paradigm: A fresco of a beau from the Villa di Arianna, Stabiae, 1st century Ad.

While the traditional view of the ancient Roman artists is that they often borrowed from, and copied Greek precedents (much of the Greek sculptures known today are in the form of Roman marble copies), more of recent analysis has indicated that Roman fine art is a highly creative pastiche relying heavily on Greek models simply as well encompassing Etruscan, native Italic, and even Egyptian visual culture. Stylistic eclecticism and applied application are the hallmarks of much Roman art.

Pliny, Ancient Rome's most of import historian concerning the arts, recorded that almost all the forms of art – sculpture, mural, portrait painting, even genre painting – were advanced in Greek times, and in some cases, more avant-garde than in Rome. Though very picayune remains of Greek wall fine art and portraiture, certainly Greek sculpture and vase painting bears this out. These forms were not likely surpassed by Roman artists in fineness of design or execution. As some other example of the lost "Golden Age", he singled out Peiraikos, "whose artistry is surpassed by merely a very few ... He painted barbershops and shoemakers' stalls, donkeys, vegetables, and such, and for that reason came to be called the 'painter of vulgar subjects'; nevertheless these works are birthday delightful, and they were sold at higher prices than the greatest paintings of many other artists."[2] The adjective "vulgar" is used here in its original definition, which means "mutual".

The Greek antecedents of Roman fine art were legendary. In the mid-5th century BC, the most famous Greek artists were Polygnotos, noted for his wall murals, and Apollodoros, the originator of chiaroscuro. The evolution of realistic technique is credited to Zeuxis and Parrhasius, who according to ancient Greek legend, are said to have once competed in a bravura display of their talents, history's earliest descriptions of trompe-fifty'œil painting.[3] In sculpture, Skopas, Praxiteles, Phidias, and Lysippos were the foremost sculptors. Information technology appears that Roman artists had much Ancient Greek art to re-create from, equally trade in art was brisk throughout the empire, and much of the Greek artistic heritage found its way into Roman art through books and teaching. Aboriginal Greek treatises on the arts are known to have existed in Roman times, though are now lost.[4] Many Roman artists came from Greek colonies and provinces.[5]

Preparation of an beast sacrifice; marble, fragment of an architectural relief, showtime quarter of the 2nd century CE; from Rome, Italia

The loftier number of Roman copies of Greek art also speaks of the esteem Roman artists had for Greek art, and possibly of its rarer and higher quality.[5] Many of the fine art forms and methods used by the Romans – such as high and low relief, free-standing sculpture, bronze casting, vase art, mosaic, cameo, coin art, fine jewelry and metalwork, funerary sculpture, perspective drawing, caricature, genre and portrait painting, landscape painting, architectural sculpture, and trompe-50'œil painting – all were developed or refined by Ancient Greek artists.[half dozen] Ane exception is the Roman bust, which did not include the shoulders. The traditional caput-and-shoulders bust may have been an Etruscan or early on Roman form.[7] Almost every artistic technique and method used past Renaissance artists 1,900 years afterward had been demonstrated past Ancient Greek artists, with the notable exceptions of oil colors and mathematically accurate perspective.[viii] Where Greek artists were highly revered in their society, almost Roman artists were anonymous and considered tradesmen. There is no recording, as in Ancient Greece, of the great masters of Roman art, and practically no signed works. Where Greeks worshipped the artful qualities of cracking art, and wrote extensively on artistic theory, Roman art was more than decorative and indicative of status and wealth, and apparently non the subject area of scholars or philosophers.[9]

Owing in function to the fact that the Roman cities were far larger than the Greek city-states in power and population, and generally less provincial, art in Ancient Rome took on a wider, and sometimes more than utilitarian, purpose. Roman civilisation assimilated many cultures and was for the nearly part tolerant of the ways of conquered peoples.[5] Roman fine art was deputed, displayed, and endemic in far greater quantities, and adapted to more uses than in Greek times. Wealthy Romans were more materialistic; they decorated their walls with art, their abode with decorative objects, and themselves with fine jewelry.

In the Christian era of the late Empire, from 350 to 500 CE, wall painting, mosaic ceiling and floor work, and funerary sculpture thrived, while full-sized sculpture in the round and panel painting died out, most likely for religious reasons.[10] When Constantine moved the uppercase of the empire to Byzantium (renamed Constantinople), Roman fine art incorporated Eastern influences to produce the Byzantine style of the tardily empire. When Rome was sacked in the 5th century, artisans moved to and establish work in the Eastern capital. The Church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople employed nearly 10,000 workmen and artisans, in a final flare-up of Roman fine art under Emperor Justinian (527–565 CE), who also ordered the cosmos of the famous mosaics of Basilica of San Vitale in the city of Ravenna.[11]

Painting [edit]

Female painter sitting on a campstool and painting a statue of Dionysus or Priapus onto a panel which is held past a boy. Fresco from Pompeii, 1st century

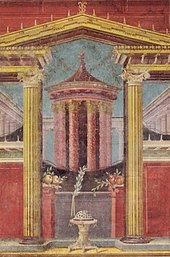

Of the vast body of Roman painting nosotros now have only a very few pockets of survivals, with many documented types not surviving at all, or doing and then simply from the very end of the period. The all-time known and most important pocket is the wall paintings from Pompeii, Herculaneum and other sites nearby, which show how residents of a wealthy seaside resort decorated their walls in the century or and so before the fatal eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD. A succession of dated styles have been defined and analysed past modernistic fine art historians beginning with August Mau, showing increasing elaboration and composure.

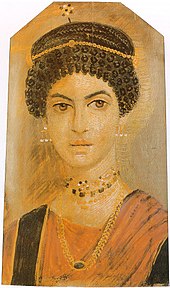

Starting in the third century Ad and finishing past about 400 we take a large body of paintings from the Catacombs of Rome, by no ways all Christian, showing the afterward continuation of the domestic decorative tradition in a version adapted - probably not profoundly adapted - for use in burial chambers, in what was probably a rather humbler social milieu than the largest houses in Pompeii. Much of Nero's palace in Rome, the Domus Aurea, survived as grottos and gives u.s. examples which we can be certain stand for the very finest quality of wall-painting in its style, and which may well have represented significant innovation in style. There are a number of other parts of painted rooms surviving from Rome and elsewhere, which somewhat aid to make full in the gaps of our cognition of wall-painting. From Roman Egypt there are a large number of what are known equally Fayum mummy portraits, bust portraits on wood added to the outside of mummies by a Romanized middle class; despite their very distinct local graphic symbol they are probably broadly representative of Roman style in painted portraits, which are otherwise entirely lost.

Nada remains of the Greek paintings imported to Rome during the fourth and 5th centuries, or of the painting on wood done in Italy during that menstruation.[4] In sum, the range of samples is confined to merely nearly 200 years out of the about 900 years of Roman history,[12] and of provincial and decorative painting. Almost of this wall painting was washed using the a secco (dry) method, but some fresco paintings also existed in Roman times. There is evidence from mosaics and a few inscriptions that some Roman paintings were adaptations or copies of earlier Greek works.[12] However, adding to the defoliation is the fact that inscriptions may be recording the names of immigrant Greek artists from Roman times, not from Aboriginal Greek originals that were copied.[eight] The Romans entirely lacked a tradition of figurative vase-painting comparable to that of the Aboriginal Greeks, which the Etruscans had emulated.

Variety of subjects [edit]

Roman painting provides a broad variety of themes: animals, still life, scenes from everyday life, portraits, and some mythological subjects. During the Hellenistic menses, it evoked the pleasures of the countryside and represented scenes of shepherds, herds, rustic temples, rural mountainous landscapes and country houses.[eight] Erotic scenes are also relatively common. In the late empire, after 200AD, early Christian themes mixed with heathen imagery survive on catacomb walls.[thirteen]

Mural and vistas [edit]

The main innovation of Roman painting compared to Greek fine art was the development of landscapes, in particular incorporating techniques of perspective, though true mathematical perspective developed i,500 years later. Surface textures, shading, and coloration are well applied just scale and spatial depth was still non rendered accurately. Some landscapes were pure scenes of nature, particularly gardens with flowers and trees, while others were architectural vistas depicting urban buildings. Other landscapes bear witness episodes from mythology, the most famous demonstrating scenes from the Odyssey.[14]

In the cultural point of view, the fine art of the ancient Eastward would accept known landscape painting only as the properties to ceremonious or armed services narrative scenes.[15] This theory is dedicated by Franz Wickhoff, is debatable. It is possible to meet bear witness of Greek knowledge of landscape portrayal in Plato's Critias (107b–108b):

... and if we await at the portraiture of divine and of man bodies equally executed by painters, in respect of the ease or difficulty with which they succeed in imitating their subjects in the opinion of onlookers, we shall find in the showtime place that every bit regards the earth and mountains and rivers and woods and the whole of sky, with the things that exist and motility therein, we are content if a homo is able to represent them with even a small-scale degree of likeness ...[xvi]

Yet life [edit]

Roman still life subjects are ofttimes placed in illusionist niches or shelves and depict a variety of everyday objects including fruit, alive and dead animals, seafood, and shells. Examples of the theme of the glass jar filled with water were skillfully painted and later on served as models for the same subject oft painted during the Renaissance and Baroque periods.[17]

Portraits [edit]

Pliny complained of the declining state of Roman portrait art, "The painting of portraits which used to transmit through the ages the authentic likenesses of people, has entirely gone out ... Indolence has destroyed the arts."[eighteen] [19]

In Greece and Rome, wall painting was not considered equally high art. The nigh prestigious form of fine art besides sculpture was console painting, i.e. tempera or encaustic painting on wooden panels. Unfortunately, since wood is a perishable material, only a very few examples of such paintings take survived, namely the Severan Tondo from c. 200 Advertisement, a very routine official portrait from some provincial government office, and the well-known Fayum mummy portraits, all from Roman Egypt, and nigh certainly not of the highest contemporary quality. The portraits were attached to burying mummies at the face, from which nigh all have now been detached. They unremarkably depict a unmarried person, showing the head, or head and upper chest, viewed frontally. The groundwork is always monochrome, sometimes with decorative elements.[20] In terms of artistic tradition, the images clearly derive more from Greco-Roman traditions than Egyptian ones. They are remarkably realistic, though variable in artistic quality, and may indicate that similar art which was widespread elsewhere but did not survive. A few portraits painted on drinking glass and medals from the later empire have survived, as have coin portraits, some of which are considered very realistic too.[21]

Gold drinking glass [edit]

Gold glass, or gilt sandwich glass, was a technique for fixing a layer of gold leaf with a design betwixt 2 fused layers of glass, adult in Hellenistic glass and revived in the 3rd century Advertizement. At that place are a very few large designs, including a very fine group of portraits from the 3rd century with added pigment, but the great bulk of the around 500 survivals are roundels that are the cut-off bottoms of wine cups or spectacles used to marking and decorate graves in the Catacombs of Rome by pressing them into the mortar. They predominantly date from the quaternary and 5th centuries. Most are Christian, though there are many heathen and a few Jewish examples. Information technology is likely that they were originally given as gifts on marriage, or festive occasions such as New Year. Their iconography has been much studied, although artistically they are relatively unsophisticated.[23] Their subjects are similar to the catacomb paintings, but with a difference balance including more portraiture. Every bit time went on there was an increment in the delineation of saints.[24] The same technique began to be used for gold tesserae for mosaics in the mid-1st century in Rome, and by the 5th century these had get the standard background for religious mosaics.

The before group are "among the most vivid portraits to survive from Early Christian times. They stare out at usa with an extraordinary stern and melancholy intensity",[25] and correspond the best surviving indications of what high quality Roman portraiture could achieve in paint. The Gennadios medallion in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, is a fine instance of an Alexandrian portrait on blueish glass, using a rather more complex technique and naturalistic style than most Tardily Roman examples, including painting onto the gold to create shading, and with the Greek inscription showing local dialect features. He had perchance been given or commissioned the piece to gloat victory in a musical competition.[26] Ane of the nearly famous Alexandrian-style portrait medallions, with an inscription in Egyptian Greek, was later mounted in an Early on Medieval crux gemmata in Brescia, in the mistaken belief that information technology showed the pious empress and Gothic queen Galla Placida and her children;[27] in fact the knot in the central figure's wearing apparel may mark a devotee of Isis.[28] This is i of a group of 14 pieces dating to the 3rd century AD, all individualized secular portraits of loftier quality.[29] The inscription on the medallion is written in the Alexandrian dialect of Greek and hence most likely depicts a family unit from Roman Arab republic of egypt.[30] The medallion has besides been compared to other works of contemporaneous Roman-Egyptian artwork, such every bit the Fayum mummy portraits.[22] It is thought that the tiny detail of pieces such every bit these can only accept been accomplished using lenses.[31] The later on glasses from the catacombs take a level of portraiture that is rudimentary, with features, hairstyles and clothes all following stereotypical styles.[32]

Genre scenes [edit]

Roman genre scenes mostly depict Romans at leisure and include gambling, music and sexual encounters.[ citation needed ] Some scenes depict gods and goddesses at leisure.[8] [12]

Triumphal paintings [edit]

Roman fresco with a banquet scene from the Casa dei Casti Amanti, Pompeii

From the 3rd century BC, a specific genre known as Triumphal Paintings appeared, as indicated by Pliny (XXXV, 22).[33] These were paintings which showed triumphal entries afterward military victories, represented episodes from the state of war, and conquered regions and cities. Summary maps were drawn to highlight key points of the entrada. Josephus describes the painting executed on the occasion of Vespasian and Titus's sack of Jerusalem:

There was also wrought gold and ivory attached virtually them all; and many resemblances of the war, and those in several ways, and variety of contrivances, affording a most lively portraiture of itself. For there was to be seen a happy land laid waste, and unabridged squadrons of enemies slain; while some of them ran away, and some were carried into captivity; with walls of great altitude and magnitude overthrown and ruined by machines; with the strongest fortifications taken, and the walls of most populous cities upon the tops of hills seized on, and an army pouring itself within the walls; as also every identify full of slaughter, and supplications of the enemies, when they were no longer able to lift up their hands in way of opposition. Burn also sent upon temples was hither represented, and houses overthrown, and falling upon their owners: rivers also, after they came out of a large and melancholy desert, ran down, non into a land cultivated, nor as potable for men, or for cattle, but through a country withal on burn upon every side; for the Jews related that such a thing they had undergone during this war. Now the workmanship of these representations was so magnificent and lively in the construction of the things, that it exhibited what had been washed to such as did non encounter it, as if they had been there really present. On the tiptop of every 1 of these pageants was placed the commander of the metropolis that was taken, and the manner wherein he was taken.[34]

These paintings have disappeared, just they likely influenced the composition of the historical reliefs carved on military sarcophagi, the Arch of Titus, and Trajan's Column. This evidence underscores the significance of landscape painting, which sometimes tended towards beingness perspective plans.

Ranuccio also describes the oldest painting to exist institute in Rome, in a tomb on the Esquiline Hill:

It describes a historical scene, on a clear background, painted in iv superimposed sections. Several people are identified, such Marcus Fannius and Marcus Fabius. These are larger than the other figures ... In the 2d zone, to the left, is a city encircled with crenellated walls, in front end of which is a large warrior equipped with an oval buckler and a feathered helmet; near him is a man in a short tunic, armed with a spear...Around these two are smaller soldiers in curt tunics, armed with spears...In the lower zone a boxing is taking place, where a warrior with oval buckler and a feathered helmet is shown larger than the others, whose weapons let to assume that these are probably Samnites.

This episode is hard to pinpoint. 1 of Ranuccio's hypotheses is that information technology refers to a victory of the delegate Fabius Maximus Rullianus during the second war against Samnites in 326 BC. The presentation of the figures with sizes proportional to their importance is typically Roman, and finds itself in plebeian reliefs. This painting is in the infancy of triumphal painting, and would accept been accomplished by the outset of the 3rd century BC to decorate the tomb.

Sculpture [edit]

Early Roman art was influenced by the art of Hellenic republic and that of the neighbouring Etruscans, themselves profoundly influenced by their Greek trading partners. An Etruscan speciality was near life size tomb effigies in terracotta, usually lying on acme of a sarcophagus chapeau propped up on one elbow in the pose of a diner in that period. As the expanding Roman Democracy began to conquer Greek territory, at first in Southern Italy and and so the entire Hellenistic world except for the Parthian far east, official and patrician sculpture became largely an extension of the Hellenistic style, from which specifically Roman elements are hard to uncrease, specially as so much Greek sculpture survives just in copies of the Roman period.[35] By the second century BC, "almost of the sculptors working in Rome" were Greek,[36] often enslaved in conquests such as that of Corinth (146 BC), and sculptors continued to be more often than not Greeks, often slaves, whose names are very rarely recorded. Vast numbers of Greek statues were imported to Rome, whether as booty or the consequence of extortion or commerce, and temples were oftentimes decorated with re-used Greek works.[37]

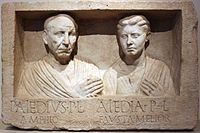

A native Italian style can be seen in the tomb monuments of prosperous centre-class Romans, which very frequently featured portrait busts, and portraiture is arguably the chief strength of Roman sculpture. In that location are no survivals from the tradition of masks of ancestors that were worn in processions at the funerals of the cracking families and otherwise displayed in the domicile, but many of the busts that survive must represent bequeathed figures, mayhap from the large family unit tombs like the Tomb of the Scipios or the later mausolea outside the city. The famous bronze caput supposedly of Lucius Junius Brutus is very variously dated, just taken as a very rare survival of Italic style under the Democracy, in the preferred medium of bronze.[38] Similarly stern and forceful heads are seen in the coins of the consuls, and in the Imperial flow coins as well every bit busts sent around the Empire to be placed in the basilicas of provincial cities were the main visual form of royal propaganda; fifty-fifty Londinium had a near-jumbo statue of Nero, though far smaller than the xxx-metre-loftier Colossus of Nero in Rome, now lost.[39] The Tomb of Eurysaces the Bakery, a successful freedman (c. 50-20 BC) has a frieze that is an unusually large example of the "plebeian" style.[xl] Imperial portraiture was initially Hellenized and highly arcadian, as in the Blacas Cameo and other portraits of Augustus.

Arch of Constantine, 315: Hadrian lion-hunting (left) and sacrificing (right), to a higher place a section of the Constantinian frieze, showing the contrast of styles.

The Romans did not generally attempt to compete with free-standing Greek works of heroic exploits from history or mythology, but from early on produced historical works in relief, culminating in the great Roman triumphal columns with continuous narrative reliefs winding around them, of which those commemorating Trajan (113 Advertisement) and Marcus Aurelius (past 193) survive in Rome, where the Ara Pacis ("Altar of Peace", xiii BC) represents the official Greco-Roman style at its virtually classical and refined, and the Sperlonga sculptures it at its about baroque. Some late Roman public sculptures developed a massive, simplified style that sometimes anticipates Soviet socialist realism. Among other major examples are the before re-used reliefs on the Arch of Constantine and the base of operations of the Cavalcade of Antoninus Pius (161),[41] Campana reliefs were cheaper pottery versions of marble reliefs and the taste for relief was from the purple period expanded to the sarcophagus.

All forms of luxury pocket-size sculpture continued to be patronized, and quality could be extremely high, as in the silver Warren Loving cup, glass Lycurgus Cup, and large cameos like the Gemma Augustea, Gonzaga Cameo and the "Groovy Cameo of France".[42] For a much wider section of the population, moulded relief ornament of pottery vessels and minor figurines were produced in bang-up quantity and oftentimes considerable quality.[43]

Afterward moving through a late 2nd century "bizarre" stage,[44] in the 3rd century, Roman art largely abandoned, or simply became unable to produce, sculpture in the classical tradition, a change whose causes remain much discussed. Even the most important imperial monuments now showed stumpy, large-eyed figures in a harsh frontal style, in simple compositions emphasizing power at the expense of grace. The contrast is famously illustrated in the Arch of Constantine of 315 in Rome, which combines sections in the new style with roundels in the earlier full Greco-Roman style taken from elsewhere, and the Four Tetrarchs (c. 305) from the new upper-case letter of Constantinople, now in Venice. Ernst Kitzinger establish in both monuments the same "stubby proportions, athwart movements, an ordering of parts through symmetry and repetition and a rendering of features and drape folds through incisions rather than modelling... The authentication of the mode wherever it appears consists of an emphatic hardness, heaviness and angularity – in short, an almost complete rejection of the classical tradition".[45]

This revolution in manner shortly preceded the period in which Christianity was adopted past the Roman state and the keen bulk of the people, leading to the finish of large religious sculpture, with big statues now only used for emperors, as in the famous fragments of a jumbo acrolithic statue of Constantine, and the 4th or 5th century Colossus of Barletta. Withal rich Christians continued to commission reliefs for sarcophagi, as in the Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, and very small sculpture, peculiarly in ivory, was continued by Christians, building on the fashion of the consular diptych.[46]

-

-

The Orator, c. 100 BC, an Etrusco-Roman statuary statue depicting Aule Metele (Latin: Aulus Metellus), an Etruscan homo wearing a Roman toga while engaged in rhetoric; the statue features an inscription in the Etruscan alphabet

-

-

-

Tomb relief of the Decii, 98–117 Advertisement

-

Portrait Bust of a Human, Ancient Rome, 60 BC

Traditional Roman sculpture is divided into five categories: portraiture, historical relief, funerary reliefs, sarcophagi, and copies of ancient Greek works.[49] Reverse to the belief of early archaeologists, many of these sculptures were big polychrome terra-cotta images, such as the Apollo of Veii (Villa Givlia, Rome), only the painted surface of many of them has worn away with time.

Narrative reliefs [edit]

While Greek sculptors traditionally illustrated armed services exploits through the employ of mythological allegory, the Romans used a more than documentary way. Roman reliefs of boxing scenes, like those on the Column of Trajan, were created for the glorification of Roman might, only besides provide starting time-hand representation of military costumes and military equipment. Trajan's column records the various Dacian wars conducted by Trajan in what is modernistic day Romania. It is the foremost example of Roman historical relief and one of the corking artistic treasures of the ancient world. This unprecedented accomplishment, over 650 pes of spiraling length, presents not simply realistically rendered individuals (over 2,500 of them), just landscapes, animals, ships, and other elements in a continuous visual history – in effect an ancient precursor of a documentary movie. It survived destruction when it was adapted every bit a base of operations for Christian sculpture.[l] During the Christian era after 300 Advertizing, the ornamentation of door panels and sarcophagi continued but full-sized sculpture died out and did non appear to be an of import element in early churches.[ten]

Minor arts [edit]

Pottery and terracottas [edit]

The Romans inherited a tradition of art in a wide range of the so-called "pocket-size arts" or decorative fine art. Most of these flourished most impressively at the luxury level, but large numbers of terracotta figurines, both religious and secular, continued to be produced cheaply, as well as some larger Campana reliefs in terracotta.[51] Roman art did non use vase-painting in the way of the ancient Greeks, but vessels in Aboriginal Roman pottery were often stylishly busy in moulded relief.[52] Producers of the millions of small oil lamps sold seem to have relied on attractive decoration to beat competitors and every subject area of Roman art except landscape and portraiture is found on them in miniature.[53]

Glass [edit]

Luxury arts included fancy Roman glass in a nifty range of techniques, many smaller types of which were probably affordable to a good proportion of the Roman public. This was certainly not the case for the most improvident types of glass, such as the cage cups or diatreta, of which the Lycurgus Cup in the British Museum is a near-unique figurative example in drinking glass that changes colour when seen with calorie-free passing through it. The Augustan Portland Vase is the masterpiece of Roman cameo drinking glass,[54] and imitated the style of the large engraved gems (Blacas Cameo, Gemma Augustea, Great Cameo of France) and other hardstone carvings that were also most popular around this time.[55]

Mosaic [edit]

Roman mosaic was a pocket-sized art, though oftentimes on a very big scale, until the very stop of the flow, when tardily-4th-century Christians began to use it for large religious images on walls in their new big churches; in before Roman art mosaic was mainly used for floors, curved ceilings, and inside and exterior walls that were going to go wet. The famous re-create of a Hellenistic painting in the Alexander Mosaic in Naples was originally placed in a floor in Pompeii; this is much college quality work than almost Roman mosaic, though very fine panels, frequently of still life subjects in small or micromosaic tesserae take also survived. The Romans distinguished between normal opus tessellatum with tesserae mostly over 4 mm across, which was laid down on site, and finer opus vermiculatum for small panels, which is thought to have been produced offsite in a workshop, and brought to the site as a finished console. The latter was a Hellenistic genre which is plant in Italy between nearly 100 BC and 100 AD. Well-nigh signed mosaics accept Greek names, suggesting the artists remained more often than not Greek, though probably oftentimes slaves trained up in workshops. The belatedly 2nd century BC Nile mosaic of Palestrina is a very large example of the popular genre of Nilotic mural, while the 4th century Gladiator Mosaic in Rome shows several big figures in combat.[56] Orpheus mosaics, often very large, were another favourite subject area for villas, with several ferocious animals tamed by Orpheus's playing music. In the transition to Byzantine art, hunting scenes tended to take over large animal scenes.

Metalwork [edit]

Metalwork was highly adult, and clearly an essential office of the homes of the rich, who dined off silver, while oftentimes drinking from drinking glass, and had elaborate cast fittings on their piece of furniture, jewellery, and small figurines. A number of of import hoards found in the last 200 years, mostly from the more fierce edges of the late empire, have given the states a much clearer idea of Roman silver plate. The Mildenhall Treasure and Hoxne Hoard are both from East Anglia in England.[57] There are few survivals of upmarket aboriginal Roman article of furniture, simply these show refined and elegant pattern and execution.

Coins and medals [edit]

Hadrian, with "RESTITVTORI ACHAIAE" on the reverse, celebrating his spending in Achaia (Hellenic republic), and showing the quality of ordinary bronze coins that were used past the mass population, hence the wear on higher areas.

Few Roman coins attain the creative peaks of the best Greek coins, only they survive in vast numbers and their iconography and inscriptions grade a crucial source for the study of Roman history, and the development of imperial iconography, as well as containing many fine examples of portraiture. They penetrated to the rural population of the whole Empire and beyond, with barbarians on the fringes of the Empire making their ain copies. In the Empire medallions in precious metals began to be produced in pocket-sized editions as imperial gifts, which are similar to coins, though larger and usually finer in execution. Images in coins initially followed Greek styles, with gods and symbols, but in the death throes of the Republic first Pompey and so Julius Caesar appeared on coins, and portraits of the emperor or members of his family unit became standard on imperial coinage. The inscriptions were used for propaganda, and in the later on Empire the army joined the emperor equally the beneficiary.

Compages [edit]

Information technology was in the surface area of architecture that Roman art produced its greatest innovations. Considering the Roman Empire extended over then great of an area and included then many urbanized areas, Roman engineers developed methods for citybuilding on a 1000 scale, including the use of concrete. Massive buildings similar the Pantheon and the Colosseum could never accept been constructed with previous materials and methods. Though physical had been invented a thousand years earlier in the Near E, the Romans extended its employ from fortifications to their almost impressive buildings and monuments, capitalizing on the cloth'south forcefulness and low cost.[58] The physical cadre was covered with a plaster, brick, stone, or marble veneer, and decorative polychrome and gold-gilded sculpture was often added to produce a dazzling upshot of power and wealth.[58]

Because of these methods, Roman architecture is legendary for the durability of its construction; with many buildings notwithstanding standing, and some all the same in use, mostly buildings converted to churches during the Christian era. Many ruins, however, accept been stripped of their marble veneer and are left with their concrete core exposed, thus appearing somewhat reduced in size and grandeur from their original appearance, such as with the Basilica of Constantine.[59]

During the Republican era, Roman architecture combined Greek and Etruscan elements, and produced innovations such equally the round temple and the curved curvation.[60] As Roman power grew in the early on empire, the start emperors inaugurated wholesale leveling of slums to build grand palaces on the Palatine Loma and nearby areas, which required advances in applied science methods and large scale design. Roman buildings were and then built in the commercial, political, and social grouping known as a forum, that of Julius Caesar being the offset and several added afterwards, with the Forum Romanum being the most famous. The greatest loonshit in the Roman world, the Colosseum, was completed around 80 Advert at the far end of that forum. It held over 50,000 spectators, had retractable textile coverings for shade, and could stage massive spectacles including huge gladiatorial contests and mock naval battles. This masterpiece of Roman architecture epitomizes Roman engineering efficiency and incorporates all 3 architectural orders – Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian.[61] Less celebrated but merely as important if not more so for most Roman citizens, was the five-story insula or metropolis block, the Roman equivalent of an apartment building, which housed tens of thousands of Romans.[62]

It was during the reign of Trajan (98–117 AD) and Hadrian (117–138 AD) that the Roman Empire reached its greatest extent and that Rome itself was at the peak of its artistic glory – achieved through massive building programs of monuments, meeting houses, gardens, aqueducts, baths, palaces, pavilions, sarcophagi, and temples.[fifty] The Roman use of the arch, the use of physical building methods, the use of the dome all permitted structure of vaulted ceilings and enabled the edifice of these public spaces and complexes, including the palaces, public baths and basilicas of the "Golden Age" of the empire. Outstanding examples of dome structure include the Pantheon, the Baths of Diocletian, and the Baths of Caracalla. The Pantheon (dedicated to all the planetary gods) is the best preserved temple of ancient times with an intact ceiling featuring an open "eye" in the heart. The meridian of the ceiling exactly equals the interior radius of the building, creating a hemispherical enclosure.[59] These grand buildings later served as inspirational models for architects of the Italian Renaissance, such as Brunelleschi. By the age of Constantine (306-337 AD), the final dandy building programs in Rome took place, including the erection of the Arch of Constantine built near the Colosseum, which recycled some stone work from the forum nearby, to produce an eclectic mix of styles.[thirteen]

Roman aqueducts, likewise based on the arch, were commonplace in the empire and essential transporters of water to big urban areas. Their standing masonry remains are peculiarly impressive, such equally the Pont du Gard (featuring three tiers of arches) and the aqueduct of Segovia, serving as mute testimony to their quality of their design and construction.[61]

Come across also [edit]

- Bacchic fine art

- Byzantine art

- Erotic art in Pompeii and Herculaneum

- Latin literature

- Music of ancient Rome

- Neoclassicism

- Parthian art

- Pompeian Styles

- Roman graffiti

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ Toynbee, J. M. C. (1971). "Roman Fine art". The Classical Review. 21 (3): 439–442. doi:10.1017/S0009840X00221331. JSTOR 708631.

- ^ Sybille Ebert-Schifferer, Still Life: A History, Harry North. Abrams, New York, 1998, p. 15, ISBN 0-8109-4190-2

- ^ Ebert-Schifferer, p. xvi

- ^ a b Piper, p. 252

- ^ a b c Janson, p. 158

- ^ Piper, p. 248–253

- ^ Piper, p. 255

- ^ a b c d Piper, p. 253

- ^ Piper, p. 254

- ^ a b Piper, p. 261

- ^ Piper, p. 266

- ^ a b c Janson, p. 190

- ^ a b Piper, p. 260

- ^ Janson, p. 191

- ^ according to Ernst Gombrich.

- ^ Plato. Critias (107b–108b), trans W.R.Thou. Lamb 1925. at the Perseus Projection accessed 27 June 2006

- ^ Janson, p. 192

- ^ John Hope-Hennessy, The Portrait in the Renaissance, Bollingen Foundation, New York, 1966, pp. 71–72

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Natural History XXXV:2 trans H. Rackham 1952. Loeb Classical Library

- ^ Janson, p. 194

- ^ Janson, p. 195

- ^ a b Daniel Thomas Howells (2015). "A Catalogue of the Belatedly Antique Aureate Glass in the British Museum (PDF)." London: the British Museum (Arts and Humanities Research Quango). Accessed 2 Oct 2016, p. 7: "Other important contributions to scholarship included the publication of an all-encompassing summary of gilded drinking glass scholarship nether the entry 'Fonds de coupes' in Fernand Cabrol and Henri Leclercq's comprehensive Dictionnaire d'archéologie chrétienne et de liturgie in 1923. Leclercq updated Vopel'south catalogue, recording 512 golden glasses considered to be genuine, and developed a typological series consisting of eleven iconographic subjects: biblical subjects; Christ and the saints; various legends; inscriptions; pagan deities; secular subjects; male portraits; female portraits; portraits of couples and families; animals; and Jewish symbols. In a 1926 article devoted to the brushed technique gold glass known equally the Brescia medallion (Pl. 1), Fernand de Mély challenged the securely ingrained opinion of Garrucci and Vopel that all examples of brushed technique gold glass were in fact forgeries. The following year, de Mély's hypothesis was supported and further elaborated upon in two articles by dissimilar scholars. A example for the Brescia medallion'south authenticity was argued for, not on the basis of its iconographic and orthographic similarity with pieces from Rome (a central reason for Garrucci's dismissal), but instead for its shut similarity to the Fayoum mummy portraits from Arab republic of egypt. Indeed, this comparison was given further credence by Walter Crum's exclamation that the Greek inscription on the medallion was written in the Alexandrian dialect of Egypt. De Mély noted that the medallion and its inscription had been reported as early as 1725, far too early on for the idiosyncrasies of Graeco-Egyptian word endings to have been understood past forgers." "Comparison the iconography of the Brescia medallion with other more closely dated objects from Egypt, Hayford Peirce then proposed that brushed technique medallions were produced in the early on third century, whilst de Mély himself advocated a more than general 3rd-century date. With the actuality of the medallion more firmly established, Joseph Breck was prepared to propose a late third to early 4th century date for all of the brushed technique cobalt blue-backed portrait medallions, some of which too had Greek inscriptions in the Alexandrian dialect. Although considered genuine past the majority of scholars by this signal, the unequivocal authenticity of these spectacles was not fully established until 1941 when Gerhart Ladner discovered and published a photograph of i such medallion still in situ, where it remains to this day, impressed into the plaster sealing in an individual loculus in the Catacomb of Panfilo in Rome (Pl. 2). Shortly after in 1942, Morey used the phrase 'brushed technique' to categorize this gold glass type, the iconography existence produced through a series of small incisions undertaken with a precious stone cutter'south precision and lending themselves to a chiaroscuro-like upshot like to that of a fine steel engraving simulating brush strokes."

- ^ Beckwith, 25-26,

- ^ Grig, throughout

- ^ Honour and Fleming, Pt 2, "The Catacombs" at analogy 7.7

- ^ Weitzmann, no. 264, entry by J.D.B.; see too no. 265; Medallion with a Portrait of Gennadios, Metropolitan Museum of Art, with better epitome.

- ^ Boardman, 338-340; Beckwith, 25

- ^ Vickers, 611

- ^ Grig, 207

- ^ Jás Elsner (2007). "The Changing Nature of Roman Art and the Art Historical Problem of Style," in Eva R. Hoffman (ed), Late Antique and Medieval Art of the Medieval World, 11-eighteen. Oxford, Malden & Carlton: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-i-4051-2071-v, p. 17, Figure i.3 on p. 18.

- ^ Sines and Sakellarakis, 194-195

- ^ Grig, 207; Lutraan, 29-45 goes into considerable item

- ^ Natural History (Pliny) online at the Perseus Projection

- ^ Josephus, The Jewish Wars VII, 143-152 (Ch six Para five). Trans. William Whiston Online accessed 27 June 2006

- ^ Strong, 58–63; Henig, 66-69

- ^ Henig, 24

- ^ Henig, 66–69; Strong, 36–39, 48; At the trial of Verres, former governor of Sicily, Cicero's prosecution details his depredations of art collections at nifty length.

- ^ Henig, 23–24

- ^ Henig, 66–71

- ^ Henig, 66; Strong, 125

- ^ Henig, 73–82;Strong, 48–52, 80–83, 108–117, 128–132, 141–159, 177–182, 197–211

- ^ Henig, Chapter 6; Strong, 303–315

- ^ Henig, Affiliate viii

- ^ Strong, 171–176, 211–214

- ^ Kitzinger, ix (both quotes), more than more often than not his Ch one; Strong, 250–257, 264–266, 272–280

- ^ Strong, 287–291, 305–308, 315–318; Henig, 234–240

- ^ D.B. Saddington (2011) [2007]. "the Evolution of the Roman Majestic Fleets," in Paul Erdkamp (ed), A Companion to the Roman Army, 201-217. Malden, Oxford, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-i-4051-2153-8. Plate 12.two on p. 204.

- ^ Coarelli, Filippo (1987), I Santuari del Lazio in età repubblicana. NIS, Rome, pp 35-84.

- ^ Gazda, Elaine Grand. (1995). "Roman Sculpture and the Ethos of Emulation: Reconsidering Repetition". Harvard Studies in Classical Philology. Section of the Classics, Harvard University. 97 (Hellenic republic in Rome: Influence, Integration, Resistance): 121–156. doi:10.2307/311303. JSTOR 311303.

According to traditional art-historical taxonomy, Roman sculpture is divided into a number of distinct categories--portraiture, historical relief, funerary reliefs, sarcophagi, and copies.

- ^ a b Piper, p. 256

- ^ Henig, 191-199

- ^ Henig, 179-187

- ^ Henig, 200-204

- ^ Henig, 215-218

- ^ Henig, 152-158

- ^ Henig, 116-138

- ^ Henig, 140-150; jewellery, 158-160

- ^ a b Janson, p. 160

- ^ a b Janson, p. 165

- ^ Janson, p. 159

- ^ a b Janson, p. 162

- ^ Janson, p. 167

Sources [edit]

- Beckwith, John. Early Christian and Byzantine Fine art. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970.

- Boardman, John, The Oxford History of Classical Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Grig, Lucy. "Portraits, pontiffs and the Christianization of quaternary-century Rome." Papers of the British Schoolhouse at Rome 72 (2004): 203-379.

- --. Roman Art, Religion and Society: New Studies From the Roman Art Seminar, Oxford 2005. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2006.

- Janson, H. W., and Anthony F Janson. History of Art. 6th ed. New York: Harry North. Abrams, 2001.

- Kitzinger, Ernst. Byzantine Fine art In the Making: Chief Lines of Stylistic Development In Mediterranean Art, tertiary-seventh Century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995.

- Henig, Martin. A Handbook of Roman Fine art: A Comprehensive Survey of All the Arts of the Roman Earth. Ithaca: Cornell University Printing, 1983.

- Piper, David. The Illustrated Library of Fine art, Portland Business firm, New York, 1986, ISBN 0-517-62336-6

- Strong, Donald Emrys, J. Grand. C Toynbee, and Roger Ling. Roman Fine art. 2nd ed. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1988.

Farther reading [edit]

- Andreae, Bernard. The Fine art of Rome. New York: H. Northward. Abrams, 1977.

- Bristles, Mary, and John Henderson. Classical Art: From Hellenic republic to Rome. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Bianchi Bandinelli, Ranuccio. Rome, the Center of Power: 500 B.C. to A.D. 200. New York: G. Braziller, 1970.

- Borg, Barbara. A Companion to Roman Fine art. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, 2015.

- Brilliant, Richard. Roman Art From the Republic to Constantine. Newton Abbot, Devon: Phaidon Press, 1974.

- D'Ambra, Eve. Art and Identity in the Roman Earth. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1998.

- --. Roman Art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Kleiner, Fred S. A History of Roman Art. Belmont, CA: Thomson/Wadsworth, 2007.

- Ramage, Nancy H. Roman Fine art: Romulus to Constantine. sixth ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ : Pearson, 2015.

- Stewart, Peter. Roman Fine art. Oxford: Oxford Academy Press, 2004.

- Syndicus, Eduard. Early Christian Art. 1st ed. New York: Hawthorn Books, 1962.

- Tuck, Steven L. A History of Roman Fine art. Malden: Wiley Blackwell, 2015.

- Zanker, Paul. Roman Art. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2010.

External links [edit]

- Roman Art - World History Encyclopedia

- Ancient Rome Fine art History Resources

- Dissolution and Becoming in Roman Wall-Painting

seiglerbehopentrib.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_art

0 Response to "During the 3rd and 2nd Centuries B C the Romans Adopted This Style of Art"

Post a Comment